Next: 6 Interpreting Univariate Results

Up: 2 Fitting Genetic Models

Previous: 4 Interpreting the Mx

Index

5 Building a Variance Components Model Mx Script

We include the variance components parameterization of the basic

structural equation model for completeness. It will not be developed

and applied in as great detail as the path coefficients

parameterization because (i) it is difficult to generalize to more

complex pedigree structures or multivariate problems, and (ii) doing

so would contribute much by weight but little by insight to this

volume. Readers seeking an easy introduction to twin models in Mx

may skip this section and focus their attention on

Section 6.2.3, the path coefficients parameterization.

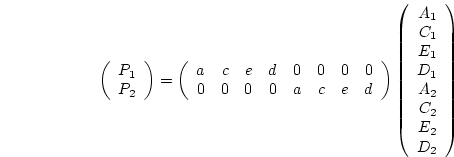

For MZ and DZ twin pairs reared in the same family, the variance

components parameterization is presented in (Figure 5.3b).

Under the simplifying assumptions of the present chapter, the  expected covariance matrix of twin pairs (

expected covariance matrix of twin pairs ( ) will be, in terms

of variance components,

) will be, in terms

of variance components,

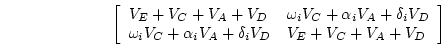

where  is 1 for twins, full sibs or adoptees reared in the

same household, but 0 for separated twins or other biological

relatives reared apart;

is 1 for twins, full sibs or adoptees reared in the

same household, but 0 for separated twins or other biological

relatives reared apart;  is 1 for MZ twin pairs, 0.5 for DZ

pairs, full sibs, or parents and offspring, and 0 for genetically

unrelated individuals; and

is 1 for MZ twin pairs, 0.5 for DZ

pairs, full sibs, or parents and offspring, and 0 for genetically

unrelated individuals; and  is 1 for MZ pairs, 0.25 for DZ

pairs or full sibs, and 0 for most other relationships. In terms of

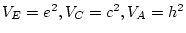

path coefficients, we need only substitute

is 1 for MZ pairs, 0.25 for DZ

pairs or full sibs, and 0 for most other relationships. In terms of

path coefficients, we need only substitute

, and

, and  .

In data on twin pairs reared together the effects of shared

environment and genetic dominance are confounded. If both additive

genetic effects and shared environmental effects contribute to

variation in a trait, the covariance of DZ twin pairs will be less

than the MZ covariance, but greater than one-half the MZ covariance.

If both additive genetic effects and dominance genetic effects

contribute to variation in a trait, the covariance of DZ pairs will be

less than one-half the MZ covariance. In terms of variance

components, therefore, a substantial dominance genetic effect will

lead to a negative estimate of the shared environmental variance

component, if a model allowing for additive genetic and shared

environmental variance components is fitted; while conversely a

substantial shared environmental effect will lead to a negative

estimate of the dominance genetic variance component, if a model

allowing for additive and dominance genetic variance components is

fitted (Martin et al., 1978).

In terms of path coefficients, however, since we are

estimating parameters

.

In data on twin pairs reared together the effects of shared

environment and genetic dominance are confounded. If both additive

genetic effects and shared environmental effects contribute to

variation in a trait, the covariance of DZ twin pairs will be less

than the MZ covariance, but greater than one-half the MZ covariance.

If both additive genetic effects and dominance genetic effects

contribute to variation in a trait, the covariance of DZ pairs will be

less than one-half the MZ covariance. In terms of variance

components, therefore, a substantial dominance genetic effect will

lead to a negative estimate of the shared environmental variance

component, if a model allowing for additive genetic and shared

environmental variance components is fitted; while conversely a

substantial shared environmental effect will lead to a negative

estimate of the dominance genetic variance component, if a model

allowing for additive and dominance genetic variance components is

fitted (Martin et al., 1978).

In terms of path coefficients, however, since we are

estimating parameters  or

or  ,

,  or

or  can never take

negative values, and so we will obtain an estimate of

can never take

negative values, and so we will obtain an estimate of  in the

presence of dominance, or

in the

presence of dominance, or  in the presence of shared

environmental effects. Additional data on separated twin pairs

(Jinks and Fulker, 1970)

or on the parents or other relatives of twins

(Fulker, 1982; Heath,

1983) are needed to resolve the effects of

shared environment and genetic dominance when both are present.

Appendix

in the presence of shared

environmental effects. Additional data on separated twin pairs

(Jinks and Fulker, 1970)

or on the parents or other relatives of twins

(Fulker, 1982; Heath,

1983) are needed to resolve the effects of

shared environment and genetic dominance when both are present.

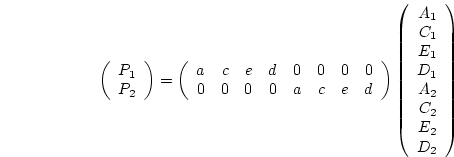

Appendix ![[*]](crossref.png) illustrates an example script for fitting a

variance components model to twin pair covariance matrices for two

like-sex twin pair groups. We estimate additive genetic, dominance

genetic and random environmental variance components in the matrices

illustrates an example script for fitting a

variance components model to twin pair covariance matrices for two

like-sex twin pair groups. We estimate additive genetic, dominance

genetic and random environmental variance components in the matrices

A, D and E. The covariance statement is the same

as for the path model example. The only change is in the calculation

group, which does not square the estimates to construct A, C, E and D.

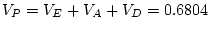

For the young male like-sex pairs, the estimates are  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  . We can calculate standardized variance components by

hand, as

. We can calculate standardized variance components by

hand, as

,

,

, and

, and

, where

, where

(which can

be read directly from the variance in the expected covariance matrix).

In this example, random environmental effects account for 20.3% of

the variance, additive genetic effects for 36.4% of the variance, and

dominance genetic effects for 43.3% of the variance of BMI in young

adult males. By

(which can

be read directly from the variance in the expected covariance matrix).

In this example, random environmental effects account for 20.3% of

the variance, additive genetic effects for 36.4% of the variance, and

dominance genetic effects for 43.3% of the variance of BMI in young

adult males. By  test of goodness-of-fit, our model gives

only a marginally acceptable fit to the data (

test of goodness-of-fit, our model gives

only a marginally acceptable fit to the data (

).

).

Next: 6 Interpreting Univariate Results

Up: 2 Fitting Genetic Models

Previous: 4 Interpreting the Mx

Index

Jeff Lessem

2002-03-21

) will be, in terms

of variance components,

) will be, in terms

of variance components,

![[*]](crossref.png) illustrates an example script for fitting a

variance components model to twin pair covariance matrices for two

like-sex twin pair groups. We estimate additive genetic, dominance

genetic and random environmental variance components in the matrices

illustrates an example script for fitting a

variance components model to twin pair covariance matrices for two

like-sex twin pair groups. We estimate additive genetic, dominance

genetic and random environmental variance components in the matrices